- Home

- Kristi Belcamino

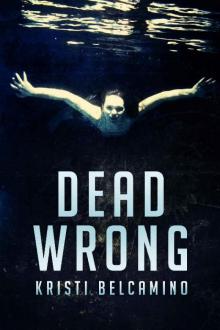

Dead Wrong

Dead Wrong Read online

DEAD WRONG

By Kristi Belcamino

This is a work of fiction. Similarities to real people, places, or events are entirely coincidental.

DEAD WRONG

First edition. December 10, 2018.

Copyright © 2018 Kristi Belcamino.

Written by Kristi Belcamino.

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE

CHAPTER THIRTY

CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE

CHAPTER THIRTY-TWO

CHAPTER THIRTY-THREE

CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR

CHAPTER THIRTY-FIVE

CHAPTER THIRTY-SIX

CHAPTER THIRTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER THIRTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER THIRTY-NINE

CHAPTER FORTY

CHAPTER FORTY-ONE

CHAPTER FORTY-TWO

CHAPTER FORTY-THREE

CHAPTER FORTY-FOUR

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Kristi Belcamino Bookshelf

DID YOU LIKE THIS BOOK?

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

CHAPTER ONE

A halo of white light shines down from the sky illuminating the girl floating facedown in the shallow water. The thumping of helicopter blades triggers a wave of goose bumps down my spine. I shrink back into my hiding spot on the beach even though the glowing circle cannot reach me. Waves spiral out from the body, making it bob unnaturally. I refuse to admit that the body is my friend Danielle.

She can’t be dead. Dead is for old people. Not seventeen-year-olds.

A small boat creeps into the sphere of light. The night goes dark. The clatter of the helicopter blades fades and within a minute is gone. Two smaller, golden beams of light dance over the water. Dark silhouettes holding the flashlights drift back and forth on the boat. Low voices carry across the water.

“We got ourselves a floater. Been a few days.”

“Grab that net.”

“Rope’s right over there.”

“What’s this?”

“Vicks. Ain’t gonna smell pretty.”

Floater. A few days. Ain’t gonna smell pretty.

This must be a mistake. My cheeks feel icy even though the night air is hot.

Voices closer, on the shore this time, break the spell. Heart pounding, I scramble back through the bushes to the main walking path around the Lake of the Isles. I start toward the cop cars parked further down the jogging trail. I’d been headed that way until the beam of the helicopter’s light lured me to the lakeshore.

Kicking up dust on the walking path, I wrap my arms around myself, darting glances at the bushes on each side of the path. I pick up my pace to a near jog.

As I get closer, the blue and red strobe lights flashing on the trees give me that same feeling I had in the bushes — that I’m dreaming and none of this is real. I stop at the mouth of the path. It’s locked off with crime scene tape.

Behind it, several police cars and a big white hearse are parked on the side of the path. A few other clumps of people hang around nearby — a few joggers, but mainly teens. Two groups of them. Some I recognize from my school — Beth and her friends. I hang back in the shadows hoping nobody notices me.

Out on the lake, an engine sputters to life. At the sound, two men wearing black jumpsuits duck under the yellow tape, tugging a gurney behind them. The word “Medical Examiner” is printed on their backs in big, blazing white letters.

The humid air presses down on me and clogs my throat.

Outside the reach of flashing lights, the dark is filled with strange shapes and shadows. A rhythmic clicking from some animal seems close by, making me draw closer to the lights.

The image of my friend’s small body glowing from the helicopter spotlight is burned into my memory. The back of her blond head. Hair fanned out in the water. Every once in a while, a sharp shoulder blade sticking out from a tank top bobbed to the surface. I squeeze my eyes tightly, hoping to rid myself of the image. Doing so only makes it worse, letting my mind run wild and imagine what I didn’t see — her eyes, wide and unseeing, her body bloated and purplish with weeds wrapped around her neck.

My eyes snap open.

This can’t be real. Danielle will come along that path from the lake any minute looking wet and tired and dirty, but alive.

I cast a quick glance at Beth and her friends. They’re crying and hugging. Another group hovers near a tree talking to a cop, a little beyond the reach of the lights so it’s hard to see their faces. They don’t go to our high school, that’s for sure. They look like those kids who hang out on the streets in Uptown with their pit bulls and cardboard signs begging for money. In the dim light, they all look the same — tattoos and leather and spikes and piercings and big black boots and Mohawks and dreadlocks. The orange glowing tips of their cigarettes leave streaks in the dark as they lift them to their mouths.

I use the hem of my shirt to wipe a glob of sweat dripping near my lip. I ran all the way from the bus stop on Lake Street.

I swat away a few mosquitos trying to feast on my bare legs. A big bushy mustached cop with a potbelly stands in front of the crime scene tape blocking the path to the lake. He clears his throat.

“Why don’t you kids take off now?” He sounds gruff, but his eyes are kind. “You’re not going to want to be here when they bring her up.”

Beth gasps. But we all ignore the cop’s warning.

I feel Beth’s glare from a few feet away.

The night’s humidity plasters her sleek black hair against her head. Beads of moisture rim her upper lip.

I have every right to be here. Same as her.

Danielle was my friend, too. Just not lately.

About an hour ago, Beth’s mother had called mine, the phone ringing through our dark, silent house. Beth’s dad was a cop. He often knew about anything bad that happened before anyone else. I’d picked up the phone in my room when I heard my mom gasp.

“They found Danielle’s body. In the Lake of the Isles.”

Body. Beth’s mother’s words echo in my ears.

On Friday, when someone at school said Danielle was missing, I figured she was at a friend’s house. Maybe she got mad at her mom or something. We didn’t talk anymore so I had no idea what was going on, but was sure it was a misunderstanding. She wasn’t missing. It definitely never crossed my mind that she could be dead.

After my mom hung up, across the hall I could hear the muffled sounds of her crying. Danielle and I had spent every minute together from first grade to eighth. She’d spent so much time at my house that when it was time to do chores, my mother would call us both as one person: “Emily and Danielle, come do the dishes.”

I listened to my mom’s choked sobs. I’d only heard my mom cry once before in my seventeen years — the time she stood over my hospital bed.

Within minutes of Beth’s mom hangi

ng up, I was gone, sneaking out of the house and on the next bus to Uptown. Now standing in the woods by the lake, I realize Beth must have snuck out, too. Although she would have driven her BMW instead of taking the bus like me. There is no way our moms would let us be here right now. I keep expecting mine to show up any second and drag me home. It’s late — past midnight — and I’m sure my mom thinks I’m in bed asleep. Maybe she’s up trying to figure out how to tell me about Danielle in the morning. I close my eyes and swallow the sour taste in my mouth.

A group of cops huddled nearby breaks apart. Some duck beneath the tape toward the water. One cop is still talking to that group of kids I don’t know, the street kids. They listen and nod their heads, looking down at their big black boots. Did they find Danielle’s body? Is that why they’re here? It’s hard to tell in the dark, but one guy wearing a newsboy cap looks familiar. I squint. A lot familiar. But from where?

Another police car drives down the narrow walking path, bushes and tree limbs screeching as they scratch its sides. This car doesn’t have a cop decal on the door, but even from here I can see the glass separating the front seat from the back.

Everything happens at once. The bushes part and the two men wearing Medical Examiner jackets pass by me with a gurney containing a lumpy black tarp.

I shrink back. My throat feels like it’s closing.

I catch snapshots, slow-motion images of everything around me:

A cop leading the street punks away to a squad car. Now I see there are three of them. They all get stuffed in the back of the unmarked car.

Beth shrieking and collapsing on the ground, her black hair drooping down over her face as she crouches on her hands and knees, her friends around her, patting her back.

A bloated, blue hand with chipped red nail polish slips out from under the tarp, off the side of the gurney, dangling, lifeless, bobbing along as it passes me. I blink. There is no hand. The bag is zipped tight.

I lean over and throw up, splashing some of my dinner onto my black Converse. I finish, bent over with my hands on my knees swallowing hard. I drag the tops of my sneakers through some leaves trying to scrape off the vomit. When I lift my head, I meet Beth’s red and swollen eyes. She bites her lip and closes her eyes.

The men have loaded the gurney into the medical examiner’s hearse. It leaves first. The other car follows. As the car passes, I see the profile of the guy in the newsboy cap in the backseat.

It’s him.

CHAPTER TWO

Back home in my bed, I lie in the dark shaking.

It can’t be true. Danielle can’t be dead.

The last time I saw her she was walking in Uptown with some street punks — with that boy I saw tonight in the newsboy cap.

It was last Thursday and I was waiting for the bus after my appointment with Dr. Shapiro. Danielle was on the sidewalk across the street walking with a group of kids. After I spotted her, it seemed like she saw me, too, so I half raised my hand in greeting, but brought it back down to my side when she quickly looked away.

When the group paused at the movie theater directly across from me, she turned and faced me. Very subtly, she put her index finger up to her lips. My shoulders lifted in a shrug. She gave the slightest nod toward the group behind her. That’s when I drew my eyes away from her and took them in.

Gutterpunks.

It’s the name we give the homeless kids who hang out in Uptown and beg for change. They come into town every summer. The rumor is they hop trains cross-country during the winter, traveling to where it’s warm. Some people call them Travelers. A few of them trace their ancestry back to gypsies. But most of them are kids who have run away or gotten kicked out of their homes.

What was Danielle doing with them? It didn’t make any sense. Before I could gesture back to her, the bus pulled up, blocking her from my view.

I remembered looking at her after I got on the bus. She was laughing, running her fingers through her new, shorter, spiky hair. She wobbled a little on her high-heeled boots and one of the punks reached out and grabbed her arm to steady her. Was she drunk? She leaned into him, pressing her face against his torn leather jacket and looked up at him, smiling with a radiance I’d never seen.

Then I knew.

She was there because of that boy.

Which didn’t make much sense. Danielle dated the boys who drove Porsches, not homeless street kids. As the bus pulled away, I leaned over to get a better look at the guy she was clinging to, but all I could see was his profile. He was long and lean and wore faded gray jeans, a long-sleeve black shirt that said Descendants and scruffy giant boots with the laces untied. A newsboy tweed cap was pulled low over his eyes, his hair hanging down to his chin.

Even from the bus I could see his fingers had tattoos and ink stretched up his hands into his shirtsleeves. He tilted his head toward hers and even though I couldn’t see his face, I could tell by Danielle’s expression that he was looking at her like every girl has ever wanted a guy to look at her. I watched until the bus pulled away. They never looked my way.

Now, lying in my bed haunted by images of Danielle’s bobbing form I know that the boy I saw last week is the same guy they put in the back of that cop car tonight with those two other gutterpunks.

Guilt swarms through me, remembering that she had called me later that same night I saw her on the streets of Uptown. It was the first time she’d called me in a year. But I’d ignored her phone call, letting it go to voice mail.

Thinking back now, I turn the slideshow of images over in my mind, trying to memorize the last time I saw her alive.

Before I fall asleep, I grab my phone and play her voice message again.

“Em ... I know we haven’t talked in a while, but there’s something I need to talk to you about. But not over the phone. I don’t know who else to call. You’re the only one who will understand. Please call me back.”

Listening now, I hear something I didn’t before: Something was bothering her and she was turning to me to talk about it. But I didn’t call her back.

IN THE MORNING, I WAKE to hear my mom and her boyfriend arguing.

Lying there staring at my mint green walls, it takes me a few seconds to remember why I feel so groggy. And to remember that Danielle is dead. No.

I creep out of bed and over to my open bedroom door, straining to hear their conversation.

The deeper voice of Sam, low, calm, and comforting filters out of my mom’s bedroom. But the door is closed so it’s impossible to make out his words. I catch snatches of my mom’s fierce, urgent whispers.

“I can’t ... too soon ... what if she ...”

And then Sam, no longer whispering, his voice commanding and firm, but gentle. “She’s stronger than you think. You’re going to have to stop treating her like — ”

The words are muffled, but I hear my mother’s response.

“She’s my daughter. You don’t understand.” My mother’s words sound bitten off, as if she spit them out between closed teeth.

Silence.

I swallow hard because they are arguing over me. I stare down at my bare feet with the purple nail polish, letting my hair hang over my eyes in a dark curtain. I shrink into my bedroom at the sound of my mother’s door opening. The creak of the stairs tells me Sam is heading downstairs.

Another pair of feet appear next to mine. These toenails are painted pale pink. My mother. She brushes my hair out of my eyes. Her hand is trembling.

“Emily, I have some bad news.”

She doesn’t know I snuck out last night.

I try to focus on my mother’s words, but can’t help feeling like I’m still dreaming and will wake any minute.

“I’m so sorry ... Beth’s mother called last night ... don’t know how to tell you ... they found Danielle ... she’s dead. They think she drowned.”

Nothing about last night seems real. But it was. That body bobbing in the lake was my oldest friend. That bag on the gurney had her body in it. I can’t ignore what my m

om is saying. I can’t escape the words. I can’t pretend I didn’t hear them.

I slump onto my bed. My mom sits beside me. I stare down at my white comforter with the small pink flowers. I know I should cry but I just feel numb.

My mother smooths my nightgown over my legs. She cringes slightly as her fingertips brush over my bony knee. Her thick eyebrows draw together and she pushes her curly brown hair back from her forehead.

“Emily, I’ll call Dr. Shapiro as soon as her office opens. I’m sure she’ll fit you in so you don’t have to wait until Friday.”

“I’m fine, mom.” I stand, brushing her hand away and examine The Sid and Nancy poster on my wall. I wait with my back to her until she sighs and stands.

At my door, she pauses. “I’ll go fix breakfast. I bought those chocolate chip waffles you like?” She says it like it’s a question.

I don’t move until I hear her footsteps on the creaky stairs.

My vision is blurry as I adjust the objects on my dresser, but the tears seem stuck with the lump in my throat. I’m so angry all of a sudden — which feels like the wrong emotion to have right now. But I’m pissed. I stop myself from sweeping all of the things off my dresser and stomping them into a million pieces.

Instead, I straighten the perfume bottle until it is exactly lined up with the stack of my favorite books — “Eleanor & Park,” “Guy in Real Life,” “The Kids” — I stack and unstack the books until the corners are perfectly straight again.

I fumble on the dresser for my round brush, sticking out of the tiny ceramic crock I’d made in seventh grade art. I wonder why I’m not crying. My oldest friend is dead. Aren’t you supposed to cry? Is this another sign that I’m a freak and not normal? Even my mom, who never cries, was crying. What is wrong with me?

I stand in front of the tiny mirror hanging on my wall near my closet door — the one that only shows my face, not my body. I avoid meeting my own eyes, big round dark blobs, as I run the brush through my droopy brown hair, pulling so hard on the snarls that tears spring to my eyes. I do it over and over, pulling the brush down through the tangles until it smarts. I don’t stop. Not even when my hair is smooth. I brush and brush, over and over, sometimes swearing in frustration at the image in the mirror.

The Suicide King

The Suicide King Blood & Roses (Vigilante Crime Series)

Blood & Roses (Vigilante Crime Series) Dark Night of the Soul

Dark Night of the Soul Forgotten Island

Forgotten Island Queen of Spades

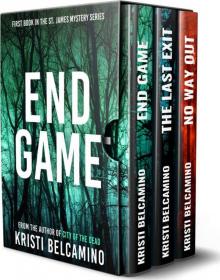

Queen of Spades The Last Exit: A St. James Mystery (St. James Mysteries Book 2)

The Last Exit: A St. James Mystery (St. James Mysteries Book 2) Black Widow

Black Widow Blood & Fire (Vigilante Crime Series Book 2)

Blood & Fire (Vigilante Crime Series Book 2) End Game

End Game Buried Secrets

Buried Secrets Death on Sunset Hill (A Tommy St. James Mystery Novella Book 2)

Death on Sunset Hill (A Tommy St. James Mystery Novella Book 2) Dark Justice

Dark Justice Dead Wrong

Dead Wrong No Way Out

No Way Out Stone Cold

Stone Cold Dark Vengeance

Dark Vengeance Dark Shadows (Gia Santella Crime Thrillers Book 11)

Dark Shadows (Gia Santella Crime Thrillers Book 11) Lone Raven

Lone Raven![[Gia Santella 01.0] Gia in the City of the Dead Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/16/gia_santella_01_0_gia_in_the_city_of_the_dead_preview.jpg) [Gia Santella 01.0] Gia in the City of the Dead

[Gia Santella 01.0] Gia in the City of the Dead City of the Dead

City of the Dead END GAME: A St. James Mystery (St. James Mysteries Book 1)

END GAME: A St. James Mystery (St. James Mysteries Book 1) Tommy St James Mysteries Boxed Set

Tommy St James Mysteries Boxed Set One-Eyed Jack

One-Eyed Jack Gia and the Lone Raven

Gia and the Lone Raven City of Angels

City of Angels Taste of Vengeance

Taste of Vengeance Gia Santella Crime Thriller Boxed Set: Books 1-3 (Gia Santella Crime Thrillers)

Gia Santella Crime Thriller Boxed Set: Books 1-3 (Gia Santella Crime Thrillers) Death under the Stone Arch Bridge

Death under the Stone Arch Bridge Blessed are the Meek

Blessed are the Meek Blessed Are Those Who Weep

Blessed Are Those Who Weep Gia in the City of the Dead

Gia in the City of the Dead Gia and the Lone Raven (Gia Santella Crime Thriller - Novella Book 4)

Gia and the Lone Raven (Gia Santella Crime Thriller - Novella Book 4) Blessed are the Merciful

Blessed are the Merciful Blessed are the Peacemakers

Blessed are the Peacemakers Gia and the Forgotten Island (Gia Santella Crime Thriller Book 2)

Gia and the Forgotten Island (Gia Santella Crime Thriller Book 2) Blessed are the Dead

Blessed are the Dead Death on Sunset Hill

Death on Sunset Hill